Libraries

Let’s see what version of python this env is running.

reticulate::py_config()## python: C:/Users/bruno/AppData/Local/r-miniconda/envs/r-reticulate/python.exe

## libpython: C:/Users/bruno/AppData/Local/r-miniconda/envs/r-reticulate/python36.dll

## pythonhome: C:/Users/bruno/AppData/Local/r-miniconda/envs/r-reticulate

## version: 3.6.12 (default, Dec 9 2020, 00:11:44) [MSC v.1916 64 bit (AMD64)]

## Architecture: 64bit

## numpy: C:/Users/bruno/AppData/Local/r-miniconda/envs/r-reticulate/Lib/site-packages/numpy

## numpy_version: 1.19.5import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import seaborn as sns

import pandas as pd

import scipy.stats as ss

import statsmodels.api as sm

import statsmodels.formula.api as smf

import os

from statsmodels.graphics.gofplots import ProbPlotSecond Post

Objectives

Define the variables used in the conclusion

In our case, we initially choose to use salary ~ sex,region region was added to test whether Simpson’s paradox was at play.

But then I augmented our analysis with a simple linear regression.

Using masks or other methods to filter the data

Visualizing the hypothesis

We were advised to use two histograms combined to get a preview of our answer.

Conclusion

Comment on our findings.

Before we start

Reservations

This is an exercise where we were supposed to ask a relevant question using the data from the IBGE(Brazil’s main data collector) database of 1970.

Our group decided to ask whether women received less than man, we expanded the analysis hoping to avoid the Simpson’s paradox.

This is just an basic inference, and it’s results are therefore only used for studying purposes I don’t believe any finding would be relevant using just this approach but some basic operations can be used in a more impact full work.

Data Dictionary

We got a Data Dictionary that will be very useful for our Analysis, it contains all the required information about the encoding of the columns and the intended format that the folks at STATA desired.

Portuguese

Descrição do Registro de Indivíduos nos EUA.

Dataset do software STATA (pago), vamos abri-lo com o pandas e transforma-lo em DataFrame.

Variável 1 – CHAVE DO INDIVÍDUO ? Formato N - Numérico ? Tamanho 11 dígitos (11 bytes) ? Descrição Sumária Identifica unicamente o indivíduo na amostra.

Variável 2 - IDADE CALCULADA EM ANOS ? Formato N - Numérico ? Tamanho 3 dígitos (3 bytes) ? Descrição Sumária Identifica a idade do morador em anos completos.

Variável 3 – SEXO ? Formato N - Numérico ? Tamanho 1 dígito (1 byte) ? Quantidade de Categorias 3 ? Descrição Sumária Identifica o sexo do morador. Categorias (1) homem, (2) mulher e (3) gestante.

Variável 4 – ANOS DE ESTUDO ? Formato N - Numérico ? Tamanho 2 dígitos (2 bytes) ? Quantidade de Categorias 11 ? Descrição Sumária Identifica o número de anos de estudo do morador. Categorias (05) Cinco ou menos, (06) Seis, (07) Sete, (08) Oito, (09) Nove, (10) Dez, (11) Onze, (12) Doze, (13) Treze, (14) Quatorze, (15) Quinze ou mais.

Variável 5 – COR OU RAÇA ? Formato N - Numérico ? Tamanho 2 dígitos (2 bytes) ? Quantidade de Categorias 6 ? Descrição Sumária Identifica a Cor ou Raça declarada pelo morador. Categorias (01) Branca, (02) Preta, (03) Amarela, (04) Parda, (05) Indígena e (09) Não Sabe.

Variável 6 – VALOR DO SALÁRIO (ANUALIZADO) ? Formato N - Numérico ? Tamanho 8 dígitos (8 bytes) ? Quantidade de Decimais 2 ? Descrição Sumária Identifica o valor resultante do salário anual do indivíduo. Categorias especiais (-1) indivíduo ausente na data da pesquisa e (999999) indivíduo não quis responder.

Variável 7 – ESTADO CIVIL ? Formato N - Numérico ? Tamanho 1 dígito (1 byte) ? Quantidade de Categorias 2 ? Descrição Sumária Dummy que identifica o estado civil declarado pelo morador. Categorias (1) Casado, (0) não casado.

Variável 8 – REGIÃO GEOGRÁFICA ? Formato N - Numérico ? Tamanho 1 dígito (1 byte) ? Quantidade de Categorias 5 ? Descrição Sumária Identifica a região geográfica do morador. Categorias (1) Norte, (2) Nordeste, (3) Sudeste, (4) Sul e (5) Centro-oeste.

English

Description of the US Individual Registry.

Dataset of the STATA software (paid), we will open it with pandas and turn it into DataFrame.

Variable 1 - KEY OF THE INDIVIDUAL? Format N - Numeric? Size 11 digits (11 bytes)? Summary Description Uniquely identifies the individual in the sample.

Variable 2 - AGE CALCULATED IN YEARS? Format N - Numeric? Size 3 digits (3 bytes)? Summary Description Identifies the age of the resident in full years.

Variable 3 - SEX? Format N - Numeric? Size 1 digit (1 byte)? Number of Categories 3? Summary Description Identifies the gender of the resident. Categories (1) men, (2) women and (3) pregnant women.

Variable 4 - YEARS OF STUDY? Format N - Numeric? Size 2 digits (2 bytes)? Number of Categories 11? Summary Description Identifies the number of years of study of the resident. Categories (05) Five or less, (06) Six, (07) Seven, (08) Eight, (09) Nine, (10) Dec, (11) Eleven, (12) Twelve, (13) Thirteen, (14 ) Fourteen, (15) Fifteen or more.

Variable 5 - COLOR OR RACE? Format N - Numeric? Size 2 digits (2 bytes)? Number of Categories 6? Summary Description Identifies the Color or Race declared by the resident. Categories (01) White, (02) Black, (03) Yellow, (04) Brown, (05) Indigenous and (09) Don’t know.

Variable 6 - WAGE VALUE (ANNUALIZED)? Format N - Numeric? Size 8 digits (8 bytes)? Number of decimals 2? Summary Description Identifies the amount resulting from the individual’s annual salary. Special categories (-1) individual absent on the survey date and (999999) individual did not want to answer.

Variable 7 - CIVIL STATE? Format N - Numeric? Size 1 digit (1 byte)? Number of Categories 2? Summary Description Dummy that identifies the marital status declared by the resident. Categories (1) Married, (0) Not married.

Variable 8 - GEOGRAPHICAL REGION? Format N - Numeric? Size 1 digit (1 byte)? Number of Categories 5? Summary Description Identifies the resident’s geographic region. Categories (1) North, (2) Northeast, (3) Southeast, (4) South and (5) Midwest.

Python

Importing the dataset from part 1

You can also dowload it from the github page from this blog

df_sex_thesis =pd.read_feather(r.file_path_linux + '/sex_thesis_assignment.feather')df_sex_thesis.info()## <class 'pandas.core.frame.DataFrame'>

## RangeIndex: 65795 entries, 0 to 65794

## Data columns (total 9 columns):

## # Column Non-Null Count Dtype

## --- ------ -------------- -----

## 0 index 65795 non-null int64

## 1 age 65795 non-null int64

## 2 sex 65795 non-null object

## 3 years_study 65795 non-null category

## 4 color_race 65795 non-null object

## 5 salary 65795 non-null float64

## 6 civil_status 65795 non-null object

## 7 region 65795 non-null object

## 8 log_salary 65795 non-null float64

## dtypes: category(1), float64(2), int64(2), object(4)

## memory usage: 4.1+ MBLet’s get going first define which variables to add to the hypothesis, to isolate the factor of salary ~ sex, if we consider that our sample of individuals is random in nature comparing the means of the individuals given their sex and seeing if there is a significant difference in their means.

A good graphic to get an idea if these effects would be significant was the bar plots used in part 1.

When working with Categorical variable it is possible to use a groupby approach to glimpse at the difference in means.

Difference in means

Using the log salary feature from post 1.

df_agg1 = df_sex_thesis.groupby('sex').mean().log_salary

df_agg1## sex

## man 9.026607

## woman 8.607023

## Name: log_salary, dtype: float64Remember that in order to transform back our log variables you can do e^variable like this e ^ 9.03 is 8321.57 but the log of the mean is not the same as the mean of the log.

df_agg2 = df_sex_thesis.groupby('sex').mean().salary

df_agg2## sex

## man 14302.491879

## woman 10642.502734

## Name: salary, dtype: float649.03 is not the same as 9.57

Therefore which one should be done first log or mean?

The most common order is log then mean, because it is the order that reduces variance the most, you can read more about this here

Group by explanation

Group by in pandas is a method that accepts a list of elements in this case just ‘sex’ and applies consequent operation in each group, in this case the mean method from a pandas DataFrame, .salary returns just the mean for the salary variable.

df_sex_thesis.groupby(['sex','region']).mean().log_salary## sex region

## man midwest 9.155421

## north 8.678263

## south 9.123554

## southeast 9.113084

## woman midwest 8.847172

## north 8.291580

## northeast 9.462870

## south 8.345867

## southeast 8.766985

## Name: log_salary, dtype: float64Adding standard deviations

df_sex_thesis.groupby(['sex']).std().log_salary## sex

## man 1.397496

## woman 2.009225

## Name: log_salary, dtype: float64These are really big Standard deviations! Remembering from stats that +2 SD’s gives about a 95% confidence interval we are not even close.

Combining mean and std using pandas agg method.

df_agg =df_sex_thesis.groupby(['sex']).agg(['mean','std']).log_salaryCalculating boundaries

df_agg['lower_bound'] = df_agg['mean'] - df_agg['std'] * 2

df_agg['upper_bound'] = df_agg['mean'] + df_agg['std'] * 2df_agg## mean std lower_bound upper_bound

## sex

## man 9.026607 1.397496 6.231615 11.821599

## woman 8.607023 2.009225 4.588573 12.625473Cool, but to verbose to be repeated multiple times, it is better to convert this series of operations into a function.

def groupby_bound(df,groupby_variables,value_variables):

df_agg = df.groupby(groupby_variables).agg(['mean','std'])[value_variables]

df_agg['lower_bound'] = df_agg['mean'] - df_agg['std'] * 2

df_agg['upper_bound'] = df_agg['mean'] + df_agg['std'] * 2

return df_agggroupby_bound(df=df_sex_thesis,groupby_variables='sex',value_variables='log_salary')## mean std lower_bound upper_bound

## sex

## man 9.026607 1.397496 6.231615 11.821599

## woman 8.607023 2.009225 4.588573 12.625473Let’s try to find the difference in salary on some strata of the population.

groupby_bound(df=df_sex_thesis,groupby_variables=['sex','region'],value_variables='log_salary')## mean std lower_bound upper_bound

## sex region

## man midwest 9.155421 1.192631 6.770160 11.540683

## north 8.678263 1.733378 5.211507 12.145019

## south 9.123554 1.426591 6.270371 11.976736

## southeast 9.113084 1.226845 6.659395 11.566773

## woman midwest 8.847172 1.575228 5.696717 11.997627

## north 8.291580 2.470543 3.350495 13.232665

## northeast 9.462870 1.172049 7.118773 11.806968

## south 8.345867 2.461307 3.423253 13.268482

## southeast 8.766985 1.639338 5.488309 12.045660No.

groupby_bound(df=df_sex_thesis,groupby_variables=['sex','civil_status'],value_variables='log_salary')## mean std lower_bound upper_bound

## sex civil_status

## man married 9.173335 1.247871 6.677593 11.669077

## not_married 8.810261 1.567870 5.674521 11.946001

## woman married 8.487709 2.263061 3.961586 13.013831

## not_married 8.771966 1.578347 5.615272 11.928659No.

groupby_bound(df=df_sex_thesis,groupby_variables=['sex','civil_status'],value_variables='log_salary')## mean std lower_bound upper_bound

## sex civil_status

## man married 9.173335 1.247871 6.677593 11.669077

## not_married 8.810261 1.567870 5.674521 11.946001

## woman married 8.487709 2.263061 3.961586 13.013831

## not_married 8.771966 1.578347 5.615272 11.928659No.

groupby_bound(df=df_sex_thesis,groupby_variables=['sex','color_race'],value_variables='log_salary')## mean std lower_bound upper_bound

## sex color_race

## man black 8.885541 1.215289 6.454962 11.316119

## brown 8.878127 1.348974 6.180179 11.576076

## indigenous 7.480596 3.328801 0.822994 14.138197

## white 9.215328 1.369700 6.475927 11.954728

## yellow 9.503222 1.398690 6.705843 12.300601

## woman black 8.617966 1.683712 5.250543 11.985389

## brown 8.518060 2.025707 4.466647 12.569473

## indigenous 7.623917 3.342682 0.938553 14.309282

## white 8.696991 2.001864 4.693263 12.700718

## yellow 8.904886 1.877233 5.150420 12.659351No.

groupby_bound(df=df_sex_thesis,groupby_variables=['sex','years_study'],value_variables='log_salary')## mean std lower_bound upper_bound

## sex years_study

## man 5.0 8.702990 1.495661 5.711668 11.694312

## 6.0 8.836372 1.285517 6.265338 11.407407

## 7.0 8.883292 1.302857 6.277578 11.489006

## 8.0 8.939945 1.342110 6.255724 11.624166

## 9.0 8.873640 1.292672 6.288296 11.458984

## 10.0 9.064804 1.122187 6.820430 11.309177

## 11.0 9.182335 1.163925 6.854486 11.510184

## 12.0 9.274507 1.187977 6.898553 11.650462

## 13.0 9.308213 1.651300 6.005613 12.610812

## 14.0 9.563542 1.295638 6.972267 12.154817

## 15.0 10.083954 1.334792 7.414369 12.753538

## woman 5.0 8.150536 2.574328 3.001881 13.299191

## 6.0 8.577851 1.854171 4.869508 12.286194

## 7.0 8.572043 1.743439 5.085165 12.058921

## 8.0 8.480459 1.952266 4.575927 12.384991

## 9.0 8.609875 1.583736 5.442403 11.777346

## 10.0 8.735525 1.403048 5.929428 11.541622

## 11.0 8.755282 1.518318 5.718647 11.791918

## 12.0 8.906622 1.505541 5.895540 11.917705

## 13.0 8.963868 1.555327 5.853213 12.074523

## 14.0 9.146458 1.263748 6.618962 11.673954

## 15.0 9.572653 1.228241 7.116171 12.029134Also no.

Does that mean that there were no Gender pay differences in Brazil in 1970?

No, it just means that there were no signs of this difference when looking at the whole population combined with one extra factor, but what if we combine all factors and isolate each influence in the salary? This would be a way to analyse the Ceteris Paribus(all else equal) effect of each feature in the salary, here is where Linear Regression comes in.

Linear Regression

But what is Linear Regression? you might ask, wasn’t it just one method for prediction? Not really, Linear Regression coefficients are really useful for hypothesis testing, meaning that tossing everything at it and then interpreting the results that come out without having to individually compare each feature pair, while also capturing the effect that all features have simultaneously.

Is Linear Regression always perfect? No. In fact most of the time the results are a little biased or a underestimate the variance or are just flat out wrong.

To understand the kinds of errors we might face when doing a linear regression we can use the Gauss Markov Theorem.

Terminology:

Predictor/Independent Variable: Theses are the features e.g sex,years_study, region we can have p predictors where p = n -1 and n is the numbers of rows our dataset possesses in this case 65795 rows are present.

Predicted/Dependent variable: This is the single “column” also called ‘target’ that we are modeling in this case we can use either log_salary or salary.

for a more in depth read this great blog post and for a more in depth usage in R and Python

Linearity

To get good results using Linear Regression the relationship of the Predictors and the Predicted variable has to be a linear relationship, to check for Linearity it is possible to use a simple line plot, and look for patterns like a parabola that would indicate that the Predictor has a quadratic relationship with the Dependent variable, there are ways of fixing non-linear relationships like we did with log_salary or by taking the power of the Predictor.

Linearity can easily be tested for numerical Predictors, categorical predictors are harder to test, so in our case we only checked the age feature.

Now it is time to flex these matplotlib graphs…

x = df_sex_thesis['age']

y = df_sex_thesis['log_salary']

plt.scatter(x, y)

z = np.polyfit(x, y, 1)

p = np.poly1d(z)

plt.plot(x,p(x),"r--")

plt.show()

It seems age is not a great fit let’s try to also log age as well.

x = np.log(df_sex_thesis['age'])

y = df_sex_thesis['log_salary']

plt.scatter(x, y)

z = np.polyfit(x, y, 1)

p = np.poly1d(z)

plt.plot(x,p(x),"r--")

plt.show()

Better but still close to no impact, maybe if we filter our sample to just the earning population, we can improve on it, we can call theses filters ‘masks’ in pandas.

df_filter = df_sex_thesis[df_sex_thesis['log_salary']> 2]df_filter## index age sex ... civil_status region log_salary

## 0 0 53 man ... married north 11.060384

## 1 1 49 woman ... married north 9.427336

## 2 2 22 woman ... not_married northeast 8.378713

## 3 3 55 man ... married north 11.478344

## 4 4 56 woman ... married north 11.969090

## ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ...

## 65790 66465 34 woman ... married midwest 9.427336

## 65791 66466 40 man ... married midwest 7.793999

## 65792 66467 36 woman ... married midwest 7.793999

## 65793 66468 27 woman ... married midwest 8.617075

## 65794 66469 37 man ... married midwest 6.134157

##

## [63973 rows x 9 columns]x = df_filter['age']

y = df_filter['log_salary']

plt.scatter(x, y)

z = np.polyfit(x, y, 1)

p = np.poly1d(z)

plt.plot(x,p(x),"r--")

plt.show()

There is some slight improvement, it is a good question whether to filter otherwise sane values, the point is that the entire analysis would change, changing to salary ~ sex in the earning population in 1970 in Brazil instead of the salary ~ sex for the whole population in 1970 in Brazil.

I think in both cases analyzing the Gender Pay Gap would be interesting it is even possible to split the hypothesis in two, analysing if Men and Women earn the same, and if Men and Women are have the same employment rate.

So for here on out We are analyzing just the Gender Pay Difference of employed people.

Random

This is a vital hypotheses it means that the observations(rows) were chosen at random for the entire Brazilian population, in this case We choose to trust that IBGE did a good job, if IBGE failed to correctly sample the population or if we mess to much with our filters we risk invalidating the whole process, yes that is right, if you don’t respect this hypothesis everything you have analysed is worthless.

Non-Collinearity

The effect of each Predictors is reduced when you introduce Colinear predictors, you are spliting the effect between the Predictors whenever a new predictor is added, meaning that you are in the worst case only calculating half of the coefficient, Collinearity always happens, Women live more so age is related to Sex, therefore age ‘steals’ part of the calculated effect from Sex, the more variables you introduce to your Linear Regression model the more that Collinearity plagues your estimations, everything is correlated.

So be careful when doing Linear Regression for estimating Ceteris Paribus effects so that you don’t introduce too many features or features that are too correlated with you hypothesis, remember that our hypothesis is Salary ~ Sex.

A good way too know if you are introducing too much Collinearity is looking at the heatmap.

corr = pd.get_dummies(df_sex_thesis[['sex','age']]).corr()

sns.heatmap(corr)

This is quite cloudy let’s get rid of the Sex interaction with itself.

We are using a really cool pandas operation inspired this stack overflow answer, and combining it with the negate operator ‘~’ effectively selecting just the columns that don’t start with sex.

new_corr = corr.loc[:,~corr.columns.str.startswith('sex')]

sns.heatmap(new_corr)

Very little correlation, we are fine.

Once again we don’t usually calculate the correlation between Categorical Variables.

Exogeneity

If violated this hypothesis blasts your study into oblivion, Exogeneity is a one way road, your Independent Variables influence your Dependent Variable, and that is it.

Discussion on whether we are violating this assumption creates really cool intellectual pursuits, Nobel’s were won discovering if there was some violation to this assumption see Trygve_Haavelmo.

In our case let’s hypothesize for all variables

Sex ~ Salary - Maybe people that get richer/poorer change Sex, probably not.

Age ~ Salary - You can’t buy year with money .

Years Study ~ Salary - Possible but this probably only happen to the latter years of education, still worth considering.

Color/Race ~ Salary - No.

Civil Status ~ Salary - Yes I can see that, taking this feature out.

Region ~ Salary - Do richer people migrate to richer regions? I think so, taking this feature out.

It is also nice to notice that this may be reason why we call the Predicted Variable the Independent Variable.

Homoscedasticity / Homogeneity of Variance/ Assumption of Equal Variance

Assumption of Equal Variance of predicted values means that for any value for the whole distribution of the Dependent Variable the estimated values remain equally distributted, meaning that we are as sure on our predictions for 1000 moneys as for 100000 moneys this assumption is really hard to adhere.

If broken the variance of the coefficients may be under or over estimated, meaning that we may fail to consider relevant features or consider wrongly irrelevant features, there are many formal statistical tests for this assumption let’s use scipy’s Bartlett’s test for homogeneity of variances where Ho is Homoscedasticity confirmation meaning we hope for p-values < 0.05.

We used a significance level of 5% for this assignment.

ss.bartlett(df_filter['log_salary'],df_filter['age'])## BartlettResult(statistic=232468.57113474328, pvalue=0.0)Don’t reject H0 -> ok

Another way to check this assumption is using tests called Breusch-Pagan and Goldfeld-Quandt post fitting the linear model.

Fitting the linear regression

Fitting the linear regression using yet another library called statsmodels.

mod = smf.ols(formula='log_salary ~ sex + age + years_study + color_race', data=df_filter)

model_fit = mod.fit()

print(model_fit.summary())## OLS Regression Results

## ==============================================================================

## Dep. Variable: log_salary R-squared: 0.133

## Model: OLS Adj. R-squared: 0.133

## Method: Least Squares F-statistic: 613.6

## Date: Thu, 21 Jan 2021 Prob (F-statistic): 0.00

## Time: 01:05:49 Log-Likelihood: -81546.

## No. Observations: 63973 AIC: 1.631e+05

## Df Residuals: 63956 BIC: 1.633e+05

## Df Model: 16

## Covariance Type: nonrobust

## ============================================================================================

## coef std err t P>|t| [0.025 0.975]

## --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

## Intercept 8.3200 0.019 440.777 0.000 8.283 8.357

## sex[T.woman] -0.2125 0.007 -30.970 0.000 -0.226 -0.199

## years_study[T.6.0] 0.1520 0.020 7.756 0.000 0.114 0.190

## years_study[T.7.0] 0.1728 0.018 9.441 0.000 0.137 0.209

## years_study[T.8.0] 0.1721 0.014 12.391 0.000 0.145 0.199

## years_study[T.9.0] 0.1395 0.019 7.449 0.000 0.103 0.176

## years_study[T.10.0] 0.2414 0.018 13.444 0.000 0.206 0.277

## years_study[T.11.0] 0.3314 0.009 35.414 0.000 0.313 0.350

## years_study[T.12.0] 0.3826 0.018 21.100 0.000 0.347 0.418

## years_study[T.13.0] 0.5989 0.025 24.032 0.000 0.550 0.648

## years_study[T.14.0] 0.6619 0.025 25.988 0.000 0.612 0.712

## years_study[T.15.0] 1.0396 0.013 78.438 0.000 1.014 1.066

## color_race[T.brown] 0.0487 0.013 3.696 0.000 0.023 0.075

## color_race[T.indigenous] 0.0587 0.040 1.451 0.147 -0.021 0.138

## color_race[T.white] 0.1805 0.013 13.736 0.000 0.155 0.206

## color_race[T.yellow] 0.2401 0.050 4.776 0.000 0.142 0.339

## age 0.0129 0.000 40.197 0.000 0.012 0.014

## ==============================================================================

## Omnibus: 14771.140 Durbin-Watson: 1.806

## Prob(Omnibus): 0.000 Jarque-Bera (JB): 45603.025

## Skew: -1.188 Prob(JB): 0.00

## Kurtosis: 6.386 Cond. No. 584.

## ==============================================================================

##

## Notes:

## [1] Standard Errors assume that the covariance matrix of the errors is correctly specified.Looking at the results, it is possible that there isGender Pay Gap, calculating the difference in estimated salaries done by

- plus intercept + e ^ beta_variable = 5077.12

- minus intercept 4105.16

- equals 971.96.

There is a 971.96 difference between men and women salaries in the earning population of Brazil in 1970 quite significant at 7.59% of the mean salary at the time.

Linear Regression plots

Using the code from this excellent post and combining it with the understanding from this post.

# fitted values (need a constant term for intercept)

model_fitted_y = model_fit.fittedvalues

# model residuals

model_residuals = model_fit.resid

# normalized residuals

model_norm_residuals = model_fit.get_influence().resid_studentized_internal

# absolute squared normalized residuals

model_norm_residuals_abs_sqrt = np.sqrt(np.abs(model_norm_residuals))

# absolute residuals

model_abs_resid = np.abs(model_residuals)

# leverage, from statsmodels internals

model_leverage = model_fit.get_influence().hat_matrix_diag

# cook's distance, from statsmodels internals

model_cooks = model_fit.get_influence().cooks_distance[0]Initializing some variables. ### Residual plot

plot_lm_1 = plt.figure(1)

plot_lm_1.axes[0] = sns.residplot(model_fitted_y, 'log_salary', data=df_filter,

lowess=True,

scatter_kws={'alpha': 0.5},

line_kws={'color': 'red', 'lw': 1, 'alpha': 0.8})## C:\Users\bruno\AppData\Local\R-MINI~1\envs\R-RETI~1\lib\site-packages\seaborn\_decorators.py:43: FutureWarning: Pass the following variables as keyword args: x, y. From version 0.12, the only valid positional argument will be `data`, and passing other arguments without an explicit keyword will result in an error or misinterpretation.

## FutureWarningplot_lm_1.axes[0].set_title('Residuals vs Fitted')

plot_lm_1.axes[0].set_xlabel('Fitted values')

plot_lm_1.axes[0].set_ylabel('Residuals')

# annotations

abs_resid = model_abs_resid.sort_values(ascending=False)

abs_resid_top_3 = abs_resid[:3]

for i in abs_resid_top_3.index:

plot_lm_1.axes[0].annotate(i,

xy=(model_fitted_y[i],

model_residuals[i]));Here we are looking for the red line to get as close to the doted black line meaning that our Predictors would have a perfectly linear relationship with our Dependent variable following the assumption of linearity.

I think we are close enough.

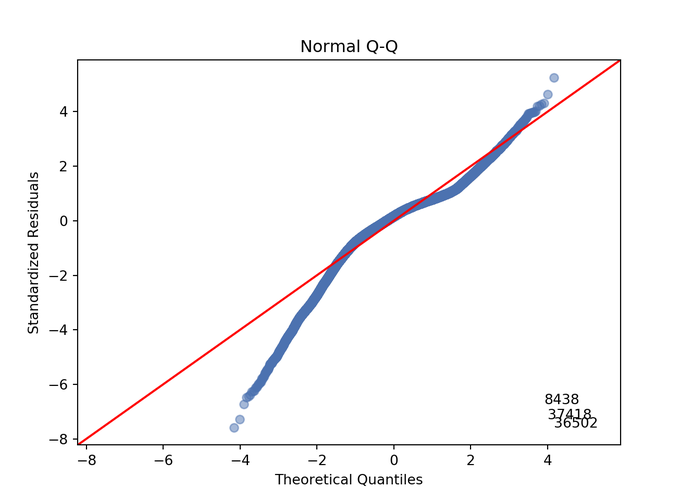

QQ plot

QQ = ProbPlot(model_norm_residuals)

plot_lm_2 = QQ.qqplot(line='45', alpha=0.5, color='#4C72B0', lw=1)

plot_lm_2.axes[0].set_title('Normal Q-Q')

plot_lm_2.axes[0].set_xlabel('Theoretical Quantiles')

plot_lm_2.axes[0].set_ylabel('Standardized Residuals');

# annotations

abs_norm_resid = np.flip(np.argsort(np.abs(model_norm_residuals)), 0)

abs_norm_resid_top_3 = abs_norm_resid[:3]

for r, i in enumerate(abs_norm_resid_top_3):

plot_lm_2.axes[0].annotate(i,

xy=(np.flip(QQ.theoretical_quantiles, 0)[r],

model_norm_residuals[i]));Here we are looking for the circles to get as close to the red line as possible meaning that our variables follow a normal distribution and therefore our p-values are not biased.

I think we have two problems the extremes may be a bit too distant and there are three concerning outliers.

Scale-Location Plot

plot_lm_3 = plt.figure(3)

plt.scatter(model_fitted_y, model_norm_residuals_abs_sqrt, alpha=0.5)

sns.regplot(model_fitted_y, model_norm_residuals_abs_sqrt,

scatter=False,

ci=False,

lowess=True,

line_kws={'color': 'red', 'lw': 1, 'alpha': 0.8})

plot_lm_3.axes[0].set_title('Scale-Location')

plot_lm_3.axes[0].set_xlabel('Fitted values')

plot_lm_3.axes[0].set_ylabel('$\sqrt{|Standardized Residuals|}$');

# annotations

abs_sq_norm_resid = np.flip(np.argsort(model_norm_residuals_abs_sqrt), 0)

abs_sq_norm_resid_top_3 = abs_sq_norm_resid[:3]

for i in abs_norm_resid_top_3:

plot_lm_3.axes[0].annotate(i,

xy=(model_fitted_y[i],

model_norm_residuals_abs_sqrt[i]));This is the graph where we check the homoscedasticity assumption, we want the red line to be as straight as possible meaning that our Predictor variance is constant among the Dependent Variable values.

I think it is fine.

Leverage plot

plot_lm_4 = plt.figure(4)

plt.scatter(model_leverage, model_norm_residuals, alpha=0.5)

sns.regplot(model_leverage, model_norm_residuals,

scatter=False,

ci=False,

lowess=True,

line_kws={'color': 'red', 'lw': 1, 'alpha': 0.8})

plot_lm_4.axes[0].set_xlim(0, 0.005)## (0.0, 0.005)plot_lm_4.axes[0].set_ylim(-3, 5)## (-3.0, 5.0)plot_lm_4.axes[0].set_title('Residuals vs Leverage')

plot_lm_4.axes[0].set_xlabel('Leverage')

plot_lm_4.axes[0].set_ylabel('Standardized Residuals')

# annotations

leverage_top_3 = np.flip(np.argsort(model_cooks), 0)[:3]

for i in leverage_top_3:

plot_lm_4.axes[0].annotate(i,

xy=(model_leverage[i],

model_norm_residuals[i]))

# shenanigans for cook's distance contours

def graph(formula, x_range, label=None):

x = x_range

y = formula(x)

plt.plot(x, y, label=label, lw=1, ls='--', color='red')

p = len(model_fit.params) # number of model parameters

graph(lambda x: np.sqrt((0.5 * p * (1 - x)) / x),

np.linspace(0.000, 0.005, 50),

'Cook\'s distance') # 0.5 line## C:/Users/bruno/AppData/Local/r-miniconda/envs/r-reticulate/python.exe:1: RuntimeWarning: divide by zero encountered in true_dividegraph(lambda x: np.sqrt((1 * p * (1 - x)) / x),

np.linspace(0.000, 0.005, 50)) # 1 line## C:/Users/bruno/AppData/Local/r-miniconda/envs/r-reticulate/python.exe:1: RuntimeWarning: divide by zero encountered in true_divideplt.legend(loc='upper right');Finally in this plot we are looking for outliers, it failed on the Python version, but it should show if the outliers plague the betas enough to the point where it may be worth studying removing them.

We want the Red line to be as close as possible to the dotted line.

Looking at the R plot We can say it is fine.

At the end I am comfortable not denying our Hypothesis that Salary ~ Sex in 1970 Brazil working population.

And that is it, Statistical analysis with almost no R! .

Final Remarks

I guess my opinion is important in this post, this was really hard, Python may be an excellent Prediction based language but it lacks so much on my normal Economist features that I have easily available even when using Stata/E-Views/SAS, like look at how much code for a simple linear regression plot!

I don’t have much hope that this will improve with time, normal statistics just doesn’t get as much hype as Deep Learning and stuff I feel sorry for whoever has to learn stats alongside Python, you guys deserve a Medal! Also I applaud the guys that Developed statsmodels.formula.api it really helps!

Whoever develops with matplotlib deserves two medals, you guys make me feel dumber than when I read my first Time Series paper and that was a really low point in my self esteem, the graphs turned out great in my honest opinion.

If you liked it please share it.

Next post

In the next part we repeat everything from part 1 with a few twists in R using the tidyverse!